Prior to 1993, most clinical trials only included men as subjects because the scientists conducting the trials viewed women as complicated, fragile, or just invisible. In addition, the thalidomide scandal of the 1950s and 1960s led the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) to issue guidelines excluding “women of childbearing potential” from drug trials starting in 1977. In reality, this resulted in all women being excluded.

Removing women from research has resulted in medical treatments, and the benefits of such treatments, being geared solely toward men. Excluding women from clinical trials has also led to a lack of data on their health, ranging from a dearth of health baselines to insufficient disease diagnoses.

Women have been found to metabolize drugs differently, which can result in more adverse reactions. They are also more likely to suffer from autoimmune diseases and to exhibit different symptoms of a heart attack, such as back pain or nausea. These differences, and many others, have led to delays in care, lack of care, and/or unnecessary suffering or death.

Finally, starting in 1986, the National Institutes of Health spent 10 years slowly establishing a policy to encourage the inclusion of women in clinical research. To further correct the lack of information on women’s health care, the NIH created the Office of Research on Women’s Health in 1990. In 1993, Congress passed the NIH Revitalization Act, which requires the inclusion of women in clinical studies.

In 2016, the NIH released guidance on the consideration of sex as a biological variable (SABV) in medical research. In order to receive NIH funding, applicants are now required to factor sex into research designs and analysis and to provide strong justification for studying only one sex. A review of this policy was published in the Journal of Women’s Health in 2020, which highlighted ways SABV has been applied across different disciplines. The article also described opportunities to improve.

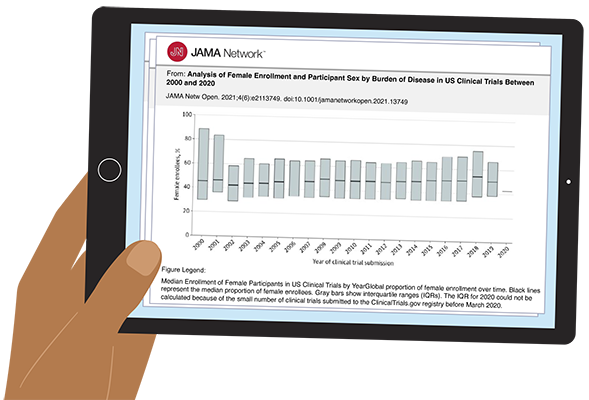

Progress has been made in the inclusion of women in clinical trials, but not nearly enough. An investigation published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2021 examined over 20,000 clinical trials with more than 5 million participants. It found that women are still underrepresented, particularly in cardiology and pediatric research. Another study found women underrepresented in psychiatric research (42% of trial participants), despite them comprising 60 percent of the patient population.

On November 13, 2023, President Joe Biden established a new White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research. Led by First Lady Jill Biden, this initiative is tasked with providing recommendations to the administration on closing the research gap for women’s health care. This initiative—along with efforts by the NIH, such as the All of Us research program that aims to increase the diversity of people in clinical research — should lead to long-needed changes in health research.

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.