Dr. Marie Curie, physicist, chemist, and the mother of two daughters, won the Nobel Prize in 1903 and 1911 for her work on radioactivity. Over a century later, in 2023, Dr. Katalin Karikó, a physiologist and mother, won the Nobel Prize for her contributions to the development of mRNA vaccines, as did Dr. Anne L’Huillier, physicist and mother, who won the prize for her work on electron dynamics. We can name many more mothers in science, yet the myth persists that motherhood is not compatible with science or with many other professional careers.

The myth impacts women before they even become mothers. In 2021, Thebaud and Taylor interviewed 57 childless STEM doctoral students and postdocs about their professional ambitions. The authors found that women were twice as likely as men to change their minds about working as professors from the time they entered their PhD programs to when they earned their doctorates. The reason given for the change came either from their adviser’s recommendation or from their personal belief that a science career and motherhood could not coexist. “Some women reported that they experienced intense pressure to reject, denigrate, or hide the mere possibility of motherhood for fear of no longer being taken seriously in the profession.” [Editor’s note: This is just one study and while it specifically looked at professorships, there are many science career options for women and mothers.]

Impact on Wages

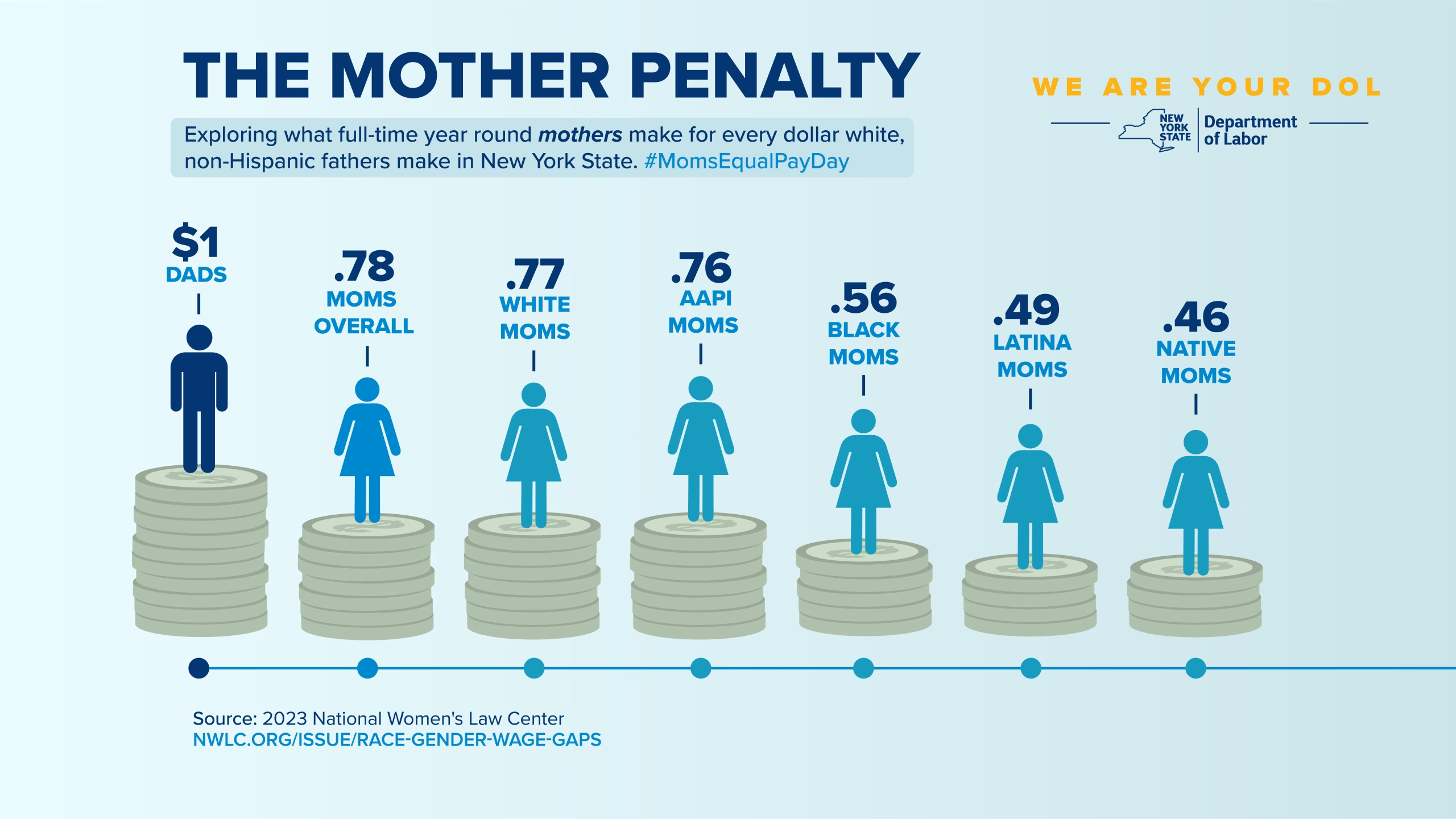

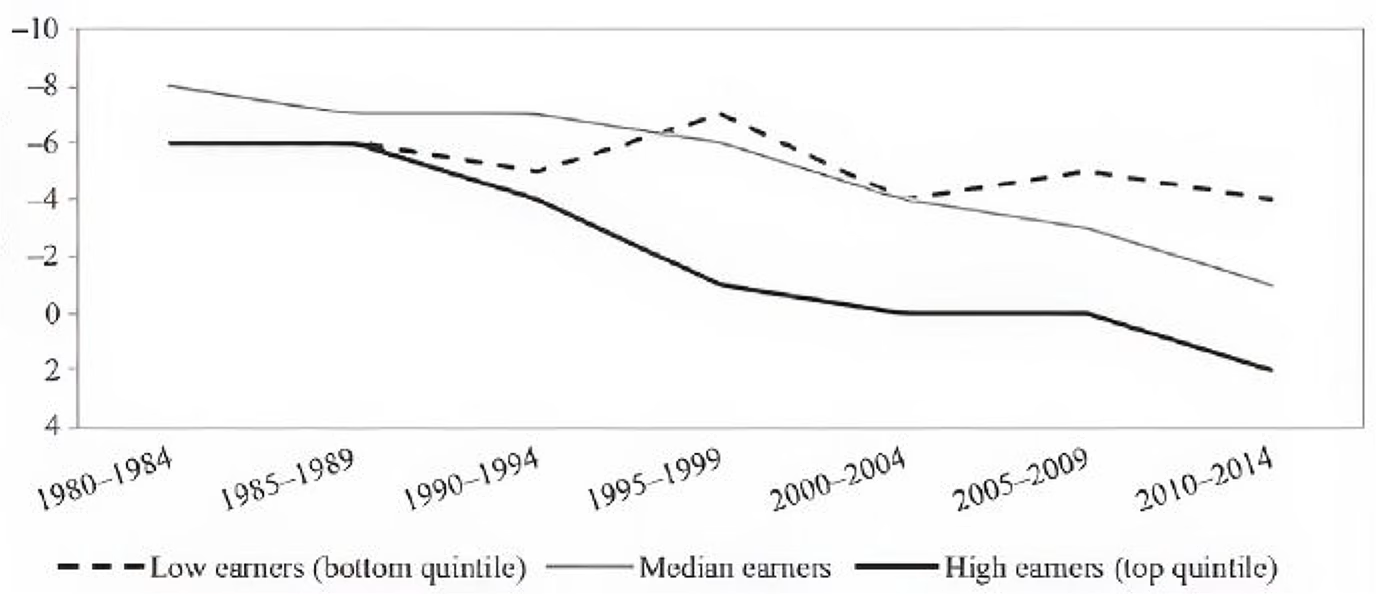

As many as one in three Americans has awareness of the gender pay gap, according to estimates, and the US Census Bureau has been tracking this inequity since 1960. However, fewer Americans understand the motherhood penalty within the gender pay gap. The former term came into prominence as a result of Budig and England’s 2001 paper entitled “The Wage Penalty for Motherhood.” In their paper, based on 1982–1993 data from a US Bureau of Labor Statistics longitudinal survey, they reported a wage penalty of 7% per child for women, with greater penalties for married women than for unmarried mothers. As reflected in the broader gender pay gap, data show a great deal of variation in the motherhood penalty across many socioeconomic factors, such as race/ ethnicity (Figure 1) and earnings levels (Figure 2).

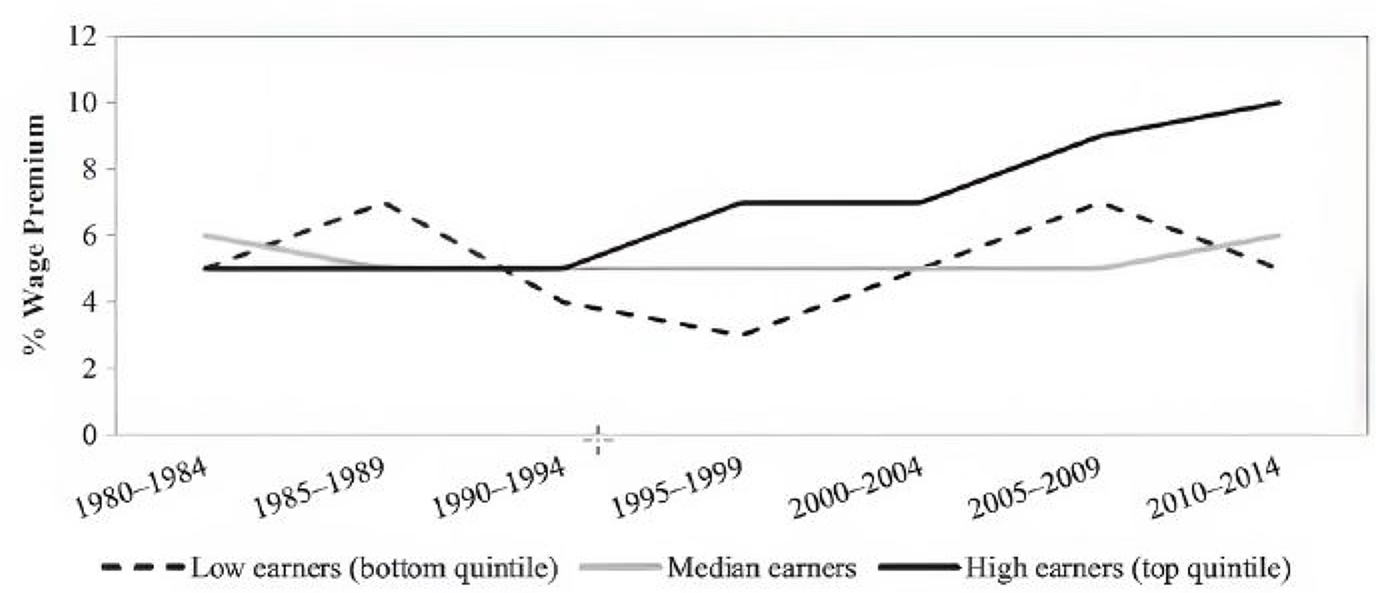

Working mothers often reduce their employment hours to meet childcare demands, which leads them to lower productivity (such as fewer publications), followed by decreased chances for promotion or tenure. In contrast to the earnings of mothers, fathers’ earnings experience little impact and, in some cases, actually increase after men become fathers, leading to the term “fatherhood premium.” Similar to the motherhood penalty, the fatherhood premium varies depending on socioeconomic factors, including income level (Figure 3).

Impact on Science

The magnitude of the motherhood penalty specific to science careers has garnered much interest due to the progressive attrition of women along the STEM pipeline. In his summary of Kim and Moser’s 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “Women in Science, Lessons from the Baby Boom,” J.C. Roach asks, “Could motherhood be the reason for the underrepresentation of women in science?”

Kim and Moser’s study uniquely examined the impact on the output of scientists who had children during arguably the most productive and innovative period in science—the Sputnik era. The authors analyzed biographical, patent, and publication data for 83,000 US scientists from the 1956 publication American Men of Science (updated to American Men and Women of Science in 1971). They found that 27% of mothers employed as academic scientists got tenure, in contrast with 48% of fathers and 46% of women without children.

With closer examination, they found a blend of good and bad news for mothers. For example, mothers had comparable tenure rates to those of other assistant professors for the first six years of their positions, an indication that the timing of productivity and tenure may be out of synch for mothers. Interestingly, mothers who survived the six-year initial period were “extremely positively selected.” While other scientists’ productivity peaked in their mid-30s, mothers experienced increased productivity after age 35 and maintained high productivity in their 40s and 50s. Mothers patented 2.5 times more and published 1.4 times more than they did before the median age at marriage than married women without children. Describing scientists in 1956, Kim and Moser summarized, “Compared to men, female scientists were more educated [84% of the women and 78% of the men had PhDs, perhaps representing labor market discrimination in the 1950s, when many graduate departments still refused to admit women], half as likely to marry, one-third as likely to have children, but half as likely to survive in science. The authors concluded, “Employment records indicate that a generation of baby boom mothers was lost to science.”

Fifty years later, Cech and Blair-Loy examined employment attrition rates. Using STEM workforce data from 2003–2010, they found that 23% of new fathers and almost twice the number (43%) of new mothers left full-time STEM employment 4–7 years after the birth or adoption of their first child. Predicted attrition rates for comparable childless men and women came in as significantly lower, 17% and 24%. Cech and Blair-Loy postulated that although contemporary fathers provided more childcare on average than those from earlier generations, the differential in the attrition between mothers and fathers in science reflected that mothers, even those employed full-time, remained the primary child-care providers.

Persistent Problem

Many governmental and private organizations have attempted to eliminate or mitigate the motherhood penalty through policies and legislation, such as laws mandating paid parental leave, but the penalty has shown remarkable staying power. In 2023, Almond et al. analyzed a large sample of US earnings data and found that women breadwinners who initially earned high salaries experienced a 60% decline in their pre-childbirth earnings compared with those of their men partners.

However, an earlier (2016) study in Sweden reported that the motherhood penalty vanished for mothers who earned more than or the same as their spouses. Thus, Almond et al. concluded, “The persistent US penalty we document is surprising but consistent with previous research that argued that the motherhood penalty is driven by both cultural and economic factors.” They noted that cultural norms typically evolve at a rate not apace with historical conditions, but they also acknowledged that norms sometimes change dramatically. The authors recommended future research to explore policies that might effectively change the cultural norms around motherhood and fatherhood.

Founded in 2019, Mothers in Science aims to:

- Support, connect, empower and increase visibility of mothers in STEMM.

- Advocate for mothers in STEMM and raise awareness of their challenges.

- Identify the systemic barriers hindering the career advancement of caregivers in STEMM to inform policy.

- Develop data-driven policies to increase caregiver inclusion and promote work-life balance in the STEMM sector.

- Break gender stereotypes and eradicate the motherhood penalty.

How to Fix It

One organization taking a two-pronged policy and sociocultural approach is Mothers in Science, a global nonprofit with a team of volunteer professionals who advocate and provide support for mothers in STEMM and design evidence-based solutions to promote inclusive policies and practices for all caregivers. One example of their work consists of an action plan for funding agencies to help working parents. The group has created the Fathers Who Care campaign as part of its multifaceted approach to addressing the motherhood penalty, and it partners with women scientist-centered organizations, such as AWIS in the United States, STEM4ALL in Europe, Asia, and the Pacific, Fatherhood Institute in the United Kingdom, and Parent in Science in Brazil and Latin America.

AWIS, of course, works to shift cultural norms by advocating for policies that support women in science, spotlighting their work, and providing a supportive community to help women stay in STEM.

The University of Minnesota’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute also supports mothers (and fathers) in science through its peer-centered coaching program Parents Leading Science (PLS, formerly Mothers Leading Science or MLS). PLS has two parallel cohorts, one oriented toward more traditional motherhood-associated experiences (yearlong program) and another toward more traditional father-associated experiences (six months long). The goal of these cohorts consists of helping participants “navigate the complex intersections of professional ambition, personal identity, and family life.” University of Pittsburgh runs a yearlong sister MLS program.

In addition, an international organization, Mums in Science, provides a “space for stories, professional connection, and encouragement” to address the attrition of scientists who are mothers. Mums in Science recently launched the Women in Stem Network, a digital platform of professional development opportunities for women scientists, including for mothers reentering the science workforce.

Taking These Lessons to Heart

Being aware of the motherhood penalty marks the first step toward mitigating it. Organizations would be wise to support and retain mothers instead of incurring the costs of hiring and training new employees. They should look at salaries of women/men/mothers/fathers to uncover and address any biases.

Motherhood also teaches skills that prove valuable in the workplace. According to a LinkedIn post by the Women in Stem Network, the experience of motherhood enhances many skills advantageous to a STEM career, such as time management, collaboration, and problem-solving.

We can all help break the myth that successful scientists cannot also be mothers (if they so choose). Motherhood makes for a lot of work, but as children grow, in-home demands lessen. Women can insist on help from their spouses and on accommodations from their employers, and the kids can even help with chores.

If you look at your long-term goals and what you hope to accomplish, you can achieve both your career aspirations and motherhood. The more women who do, the more role models will demonstrate all the possibilities and help to shift the cultural norms in science and in our broader society.

Patricia Soochan has retired as a senior program strategist at Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Prior to HHMI, she was a science assistant at the National Science Foundation, a science writer for a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, and a research and development scientist at Life Technologies. She received her BS and MS degrees in biology from George Washington University.

Patricia Soochan has retired as a senior program strategist at Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Prior to HHMI, she was a science assistant at the National Science Foundation, a science writer for a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, and a research and development scientist at Life Technologies. She received her BS and MS degrees in biology from George Washington University.

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.