Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Natural Sciences

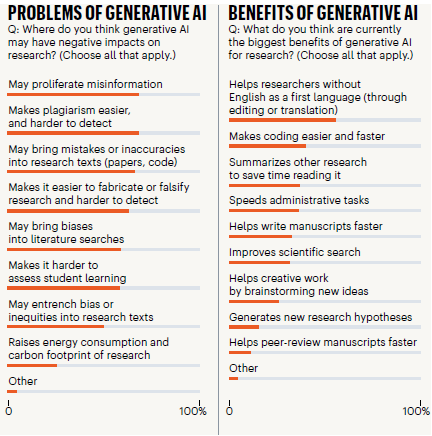

How AI is being utilized in the natural sciences is as varied as the latter’s disciplines. In 2023 Nature published the results of a global survey of 1600 science researchers on their thoughts and uses of AI. Slightly less than 50% of the respondents reported that they studied or developed AI to process data, write code, and help write papers. They were asked to articulate some of the pros and cons on the impact of machine learning and generative AI (Figures 1 A and B). About 55% of the respondents agreed that machine learning AI saves scientists time and money. Among the negative impacts, 69% agreed that machine learning AI can lead to more reliance on pattern recognition without context. Prominent among the benefits of generative AI such as ChatGPT was helping researchers for whom English was not their primary language; however, close to 70% of respondents were worried about the potential for plagiarism, mistakes, and proliferating misinformation.

In a forum in 2024, a panel of Microsoft Research AI4Science researchers described some of the ways in which AI is influencing the research enterprise in physics, materials science, cell and molecular biology, and healthcare. In healthcare, researchers are using AI as a tool for universal data structuring to unlock massive quantities of idiosyncratic and newly reported data to improve precision medicine. AI is being used to complete density functional theory in physics to elucidate nuclear structure. In the heterogeneous field of biology, adoption of AI into its research varies. For example, there are already strong protein structure prediction programs, but the work to train omics and microscopy imaging models for AI is only now emerging. AI has been able to accelerate the simulation of properties in material science and generative AI models allow for faster screening of hypothetical materials. Adoption of AI for materials screening has been propelled by the 2023 AI-assisted discovery of a new class of antibiotics by MIT researchers.

Despite the optimism about the potential scientific and medical advances with AI, there is concern about uncritical reliance on it. A 2023 paper in Nature cited several flawed AI-reliant studies that prompted the authors to ponder the possibility of AI contributing to the reproducibility crisis in science. Various sources of errors included data leakage – where there is insufficient segregation of data used to train vs test the AI system – developing and testing on small data sets, generative AI-created data, insufficient computer coding disclosure, and lack of scientific training in how to apply machine learning to test hypotheses.

AI has also impacted the world of scientific publishing, where the facile adoption of generative AI in writing papers is prompting the application of brakes or at least guardrails in manuscript submission. At the time of Nature’s 2023 survey, biomedical researchers varied in their adoption of AI by field (based on references to AI in paper titles or abstracts in Scopus), with computer science leading the way with over 25%, followed by the physical sciences around 8%, and the life sciences slightly under 5%. One editor reported problems in finding reviewers with expertise in both the science topic and AI. Publisher Elsevier has deployed its own Scopus AI that not only searches the literature but synthesizes the information into a referenced summary.

University of Michigan’s Institute for Data Science has posted on its website a guide for using generative AI for science research and publication, including technical guides for using it to learn coding and conduct data analysis. The general recommendation is that generative AI may be used for editing but not for writing papers. The guide also contains guidelines for specific journals.

Education

Students have opened a Pandora’s box of ChatGPT. Rather than fight the AI’s infiltration into the classroom, higher education is feverishly working to stay a step ahead by providing guidance for educators and staff to take advantage of it. Oregon State University, for example, has developed an alignment framework for educators on potential AI-sourced compared to human-sourced student work and Bloom’s taxonomy.

In addition to keeping up with AI, many see ways in which AI can enhance STEM education. In April 2024, Purdue University held an AI-ED Fusion symposium, which included presentations on the use of AI to train students how to leverage it for their own learning, extend learning via analogies in physics, assess multidimensional learning, enhance learning through immersive extended reality platforms, and explore ethical issues in STEM. Researchers at Cal State Fullerton and University of Southern California are exploring ways to use AI to expand and personalize online mentoring for students from historically marginalized groups. And to help STEM educators, NSF launched the EducateAI initiative to offer professional development that will facilitate inclusive AI student experiences.

AI may prove a boon for expansion of programs to teach AI development skills that employers are demanding. In fact, the February 2024 Chronicle of Higher Education’s article, “AI Will Shake up Higher Ed. Are Colleges Ready?” states that University of Wisconsin Madison plans to hire as many as 50 new faculty members in AI. AI-related job postings more than doubled on the Chronicle’s site from 2022 to 2023, but just five institutions accounted for almost half of the postings. They were Northeastern, Carnegie Mellon, and Clemson Universities and the Universities of Pennsylvania and Florida.

Reaping the benefits of AI may not come easily as technology companies and higher education have fundamentally different approaches and processes.

AI may widen inequities among students or narrow them. Read Part 3: The impact of AI on inequities.

Read the Summer 2024 AWIS Magazine article about AI roboticist, Dr. Ayanna Howard, and her work in assistive technologies.

Patricia Soochan is a senior program strategist in Data Science, Research, and Analysis in the Center for the Advancement of Science Leadership & Culture at Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). In her role, she collaborates with the Center’s programs to capture, analyze, synthesize, and communicate program-level data to promote organizational effectiveness and evaluation. Previously she shared lead responsibility for the development and execution of Inclusive Excellence (IE1&2) initiative and had lead responsibility for science education grants provided primarily to undergraduate institutions, a precursor of IE. She is a member of the Change Leaders Working Group in the Accelerating Systemic Change Network and is a contributing writer for AWIS Magazine and The Nucleus. Prior to joining HHMI, she was a science assistant at the National Science Foundation, a science writer for a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, and a research and development scientist at Life Technologies. She received her BS and MS degrees in biology from George Washington University.

Editor’s Note: The contents of this article are not affiliated with HHMI.