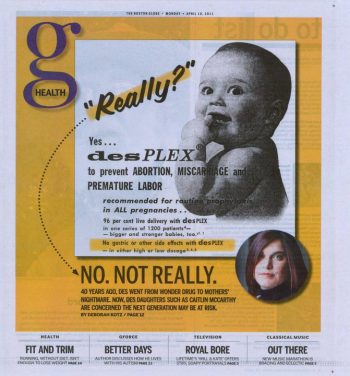

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) is a synthetic estrogen that was produced by British chemist Sir Edward Charles Dodds in 1938 and widely prescribed in the mid 20th century to pregnant women. It was advertised as a drug that could prevent miscarriages and premature labor, sold by hundreds of drug companies, and prescribed to millions of women. What no one knew until several decades later, however, is that taking DES can increase your risk for cancer, a connection established at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in 1971. Evidence has also emerged on the adverse health effects of DES on the children of mothers who took DES while pregnant, unveiling a multigenerational scandal that is still being understood.

The Wonder Drug

At first, DES was referred to as a “wonder drug.” It is now known as the “hidden Thalidomide,” due to its toxic and carcinogenic effects that have caused severe and unforeseen health issues. Medical providers prescribed DES to pregnant women who had experienced previous miscarriages, gestational diabetes, bleeding, the threat of miscarriage, or premature labor. It was prescribed as a pill, cream, or vaginal suppository, and manufacturers also included it in the formulation for prenatal vitamins. No one ever patented DES, so various pharmaceutical companies produced and sold the drug. According to the NIH, 5 to 10 million women in the United States had exposure to DES.

Harvard University conducted a clinical trial of DES in the 1940s, which showed that the drug reduced complications in pregnancy. However, this initial study did not include a control group. Despite this lack of scientific rigor, the FDA approved DES in 1947.

In the 1950s, researchers at the University of Chicago conducted a DES clinical trial involving a control group. They found that miscarriages occurred more commonly in women treated with DES and that their babies were smaller. Despite this evidence, the FDA continued to allow doctors to prescribe DES to millions of pregnant women between 1938–1971 in the United States and until the mid-1980s in parts of Europe.

In the 1960s, doctors detected clear cell adenocarcinoma— a rare type of cancer that typically occurs in the female reproductive organs—in very young women, and it was linked to DES exposure in utero. We now characterize DES as an endocrine disruptor and know that exposure to it causes problems that can continue through several generations. Research has also shown that women who took DES have a greater risk of developing breast cancer.

Many scientific, peer-reviewed articles document evidence of DES’s adverse health effects. The women exposed in utero, called DES Daughters, are 40 times more likely to develop clear cell adenocarcinoma and are also more likely to suffer from infertility, high-risk pregnancies, breast cancer, cellular abnormalities in the cervix, and cardiovascular disease, with specific associations of DES exposure to coronary artery disease and myocardial infarctions. Other suspected effects, including auto-immune disorders, await confirmation from a current, multi-generational DES study conducted by the National Cancer Institute division of the National Institutes of Health.

Caitlin McCarthy

Photo by Rory Lewis

One DES Daughter has widely shared her story and advocated for others in her situation. In 2005, Caitlin McCarthy, a Worcester public school teacher and award-winning screenwriter, discovered that she had been exposed to DES in utero when her doctor found precancerous cells in her cervix and then ordered a more thorough imaging exam known as a colposcopy. During this imaging test, the doctor noticed some structural abnormalities within seconds and asked McCarthy to share the year of her birth. McCarthy’s birth year fell between 1940 and 1971, the period when doctors often prescribed DES. All signs pointed to a likely DES exposure and the doctor just needed confirmation from McCarthy’s mother, who coincidentally had accompanied her daughter to the clinic that day: Had she taken any form of DES? Her mother acknowledged that she had been prescribed a prenatal vitamin after experiencing some bleeding during her pregnancy.

McCarthy had difficulty receiving appropriate health care to mitigate the risks of her DES exposure. She says, “I had a primary care physician who dismissed my concerns about being a DES Daughter. Another physician didn’t know about DES at all. Now she includes DES exposure in her intake form. It’s shocking that the medical community isn’t more aware of this. Doctors should proactively screen for DES exposure and follow through with cancer and fertility screenings.” The absence of immediate symptoms from DES exposure and the generational gap in health effects adds other layers of complexity to diagnosing and managing the consequences of DES exposure, especially since there are also many other factors that may contribute to cancer and fertility issues.

Medical records that confirm maternal DES may also no longer exist, in part due to the transition to electronic medical records. As McCarthy shares, “During the colposcopy, my doctor showed me the monitor, and I could see the hooded cervix, a telltale sign of DES exposure. There’s no test for DES exposure, so they rely on visuals. Unfortunately, in many cases, the medical records for the mothers of DES Daughters and Sons have been lost.”

Seeking Support

The aftermath of DES exposure is difficult to navigate, but people have formed support groups to come together in a safe space where they can share their experiences and learn from each other. One such group, DES Action, provides information for DES Mothers, Daughters, and Sons and outlines health risks that DES-exposed individuals may face. McCarthy joined this group in 2005, where she proactively shared her experience with others, but also reached many DES Daughters outside the organization by holding open conversations on her experience. McCarthy appeared on WCVB TV’s Chronicle News Magazine with another DES Daughter, Andrea Goldstein, to talk about their experiences, and she also helped organize a symposium at MGH in 2011 for the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the DES-cancer link by MGH physicians Howard Ulfelder, Arthur L. Herbst, and David C. Poskanzer. She explains, “I’ve found other people. I’ve made them feel less alone. They’ve asked me for help or questions. I’ve even been able to direct some of them to a DES lawyer.”

Such advocacy efforts have led to numerous lawsuits. In a 1981 class action suit in Massachusetts, Payton v. Abbott Laboratories, which ultimately reached the Supreme Court, plaintiffs sought damages from Abbott Laboratories for adverse health impacts caused by DES exposure. This case set the legal precedent for pharmaceutical companies accepting responsibility for product liability and for warning consumers about the risks of using their products.

In 1994, a New York jury awarded $42.3 million to 11 DES Daughters for the reproductive harm that DES caused. The Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories lawsuit in 1980 proved historic because it established the concept of market share liability: companies now must accept liability for their market share of a harmful product. Many other cases ended in settlements with the litigants although the financial details are kept private.

Taking legal action has been a challenge, however, for some patients and their offspring. To initiate legal cases, plaintiffs must pinpoint which drug company manufactured and sold the drug that affected them, and the lack of records can make this difficult to ascertain. Since adverse health effects appear decades after DES exposure, the statute of limitations may also prevent plaintiffs from making a case at all. In Enright v. Eli Lilly & Co. in 1981, the court ruled that DES manufacturers could not be held liable for harm done to the third generation.

What’s Next?

DES is a story that started in the first half of the 20th century, but its legacy continues as DES Sons and Daughters still experience adverse health effects from exposure to this synthetic hormone in utero. Research on the effects of DES exposure is continuing. However, there are still significant knowledge gaps about the long-term effects of DES on systemic conditions. As McCarthy explains, the lack of knowledge unsettles her as a DES Daughter: “I have an autoimmune disorder that isn’t in my family, and I wonder if it’s DES-related. My mother died of a rare cancer, and I always wonder if it was related to DES. There aren’t enough studies to confirm these suspicions. The lack of information leaves us wondering about the effects of DES.” Ensuring that researchers are given funding to continue investigating the effects of DES exposure could uncover new associations that are critical for early detection and treatment.

DES is a story that started in the first half of the 20th century, but its legacy continues as DES Sons and Daughters still experience adverse health effects from exposure to this synthetic hormone in utero. Research on the effects of DES exposure is continuing. However, there are still significant knowledge gaps about the long-term effects of DES on systemic conditions. As McCarthy explains, the lack of knowledge unsettles her as a DES Daughter: “I have an autoimmune disorder that isn’t in my family, and I wonder if it’s DES-related. My mother died of a rare cancer, and I always wonder if it was related to DES. There aren’t enough studies to confirm these suspicions. The lack of information leaves us wondering about the effects of DES.” Ensuring that researchers are given funding to continue investigating the effects of DES exposure could uncover new associations that are critical for early detection and treatment.

Keeping conversations about DES alive is just as important as continuing to investigate the effects of DES exposure. McCarthy has been writing a screenplay titled “Wonder Drug”— which Lori Singer plans to turn into a feature film—about a couple affected by DES. As she says, “The goal is to entertain, make an emotional impact, and raise awareness about the issue.”

Erika Minetti is a researcher at Boston University School of Medicine who investigates vascular endothelial health in a translational setting. Her work delves into the impact of cardiometabolic diseases on vascular endothelial health and into the hemodynamic effects of e-cigarettes marketed as “clear,” which have been sold since the tobacco flavoring ban was enacted in Massachusetts. Minetti graduated from Boston University with a B.A. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and an M.S. in Medical Sciences. She has been serving as the MASSAWIS Communications Committee Co-Chair since 2023. In her free time, she plays the violin with the Harvard Griffin GSAS Student Center Orchestra and enjoys lifting at the gym.

Erika Minetti is a researcher at Boston University School of Medicine who investigates vascular endothelial health in a translational setting. Her work delves into the impact of cardiometabolic diseases on vascular endothelial health and into the hemodynamic effects of e-cigarettes marketed as “clear,” which have been sold since the tobacco flavoring ban was enacted in Massachusetts. Minetti graduated from Boston University with a B.A. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and an M.S. in Medical Sciences. She has been serving as the MASSAWIS Communications Committee Co-Chair since 2023. In her free time, she plays the violin with the Harvard Griffin GSAS Student Center Orchestra and enjoys lifting at the gym.

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.