“Within our Native mythology and stories are the sciences and within the Native sciences are the mythology and stories.” A.O. Kawagley in Sharing Our Pathways, A Newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative, Alaska Federation of Natives/University of Alaska/NSF, 1996.

Dr. Wendy F. K’ah Skáahluwáa Todd, geoscientist and Native Alaskan, has come full circle on parallel and then interwoven odysseys that honor two ways of knowing science – one based on her Western training and the other on her Indigenous upbringing. She recently resigned her position as Dr. Howard Highholt Endowed Professor at University of Minnesota Duluth where she held a joint appointment in American Indian Studies and Earth and Environmental Sciences to become professor of the inaugural program in Indigenous Science and Occupational Endorsement at University of Alaska Southeast – Juneau, an Alaska Native/Native American/Native Hawaiian-serving non-tribal institution.

A Journey of Scientific Discovery

Dr. Todd’s journey began in the homeland of the Haida people, Hydaburg, in Southeast Alaska, population 380 (2020 census), of whom 318 identify as solely American Indian or Alaska Native. The long, traumatic history of the near eradication of Native American peoples and their cultures by their colonizers reaches Dr. Todd as recently as her mother, who was sent to boarding school by the US government and who is still reticent about participating in some Haida cultural traditions. Only a handful of community elders still speak the Haida language.

Dr. Todd, recalling her Haida “water people” roots, describes her journey into geoscience as “a canoe going down river and I didn’t know what was ahead.” Her academic path began when she was living in Ketchikan and her grandfather (whom she refers to as her “chanáa” in her Native Haida language) passed away and left her money to go to college. She wasn’t sure what she would study but she wanted to honor her grandfather’s wishes and so matriculated to University of Alaska Ketchikan. The first class she selected was sociology, where she didn’t do well. As part of her openness to academic topics, she selected microbiology as her next class. She found the instructor very engaging and the subject fascinating, especially as it came to life in field work when she monitored microbe content in rivers and lakes. She adds, “In Alaska, we’re always ‘in the field’ – fishing, collecting berries, harvesting – that’s our way of life. I think I liked how the microbiology class tied into what I felt was a part of my life.” This was her firsthand experience with the importance of cultural engagement via fieldwork in geoscience for Native students. Having succeeded in the course and with an interest in studying diseases, she saw herself as a future medical microbiologist.

“I was a canoe going down a river and I didn’t know what was ahead.” Dr. Wendy Todd at the start of her educational journey.

After her first microbiology course, “In Alaska, we’re always ‘in the field’ – fishing, collecting berries, harvesting – that’s our way of life. I think I liked how the microbiology class tied into what I felt was a part of my life.”

Then life happened. She got married, started a family, and moved to Portland, Oregon. After her daughter was born, she matriculated to Portland Community College, where she earned an associate’s degree. She wanted to continue her studies at Portland State University (PSU), but was unsure how she would afford it – until she learned about a scholarship from the Sealaska Heritage Institute, an organization dedicated to advancing Southeast Alaska Native cultures. The scholarship allowed her to complete her bachelor’s in molecular microbiology. She then worked as a technician in a PSU astrobiology lab studying the effect of extremophilic microbes on rock and water chemistry at Yellowstone National Park. She considered pursuing a master’s in microbiology, but working alongside grad students for six years in this lab gave her the confidence to apply for a doctorate at Oregon Graduate Institute (now Oregon Health & Science University or OHSU). This institute was part of NSF’s Science and Technology Centers: Integrative Partnerships – a program that included a focus on broadening participation for persons historically underrepresented in STEM. At OHSU, she received an NSF graduate research fellowship, which led to her discovery of hyperthermophilic bacteria that oxidizes manganese deposits at Yellowstone. She went on to earn her doctorate in environmental science and engineering and estuary and ocean systems.

A Journey of Self-Discovery

Dr. Todd found a deep connection to her culture in her study of geoscience and wanted to share this time of exciting scientific discovery with her Haida community. Well aware of the underrepresentation of Native Americans in science, she began conversations with Haida elders about incorporating Traditional Knowledge (TK) and language into her work and more broadly into science. These early conversations led to a reawakening. Her scientific journey had taken her far away from her community and while reconnecting with them, she relearned that from their perspective, education meant forced boarding school and erasure of family and culture. She says, “I was coming in excited about my work and had to step back and learn from the tribe and from the elders of what education meant and then what they expected me to do if I was going to continue to do work with Native students. What was my responsibility going to be? Understanding that just took me on my own journey of trying to teach other people who we Haida people are and what our knowledge systems mean.”

She had further lessons to learn along this part of her journey. At an education section meeting of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians conference, she learned that some Indigenous people did not want their knowledge and culture shared due to the history of extraction, misinterpretation, and appropriation by Westerners. She adds that misinterpretation is often caused by those not taking the time required to truly understand Indigenous ways of knowing and cultures. This is especially true in the sciences because the work is fast paced. Tribal communities are also concerned about repackaging of TK, for example in plant medicines, without tribal acknowledgement or sharing in commercialization revenue. She notes however that there have been recent advancements to protect TK by organizations such as the World Intellectual Property Organization. Another concern of tribal communities is the Western tendency to view Indigenous cultures as monolithic, without regard for their local context. To model acknowledgment of community ownership of the TK that she shares, she always discloses that she had permission from the elders and the tribe to share specific pieces of information.

Navigating Rough Waters

Her enthusiasm to acknowledge and incorporate her heritage into her scientific career, and to create a model using the two ways of knowing to make science more meaningful to her community, was not shared by many of her mentors or peers. She was warned her outreach would be detrimental to earning her degree. Her first paper published as a grad student was about her experience with a precollege outreach program that combined TK and Western science. It was summarily dismissed by a mentor as “not science.” She was advised to omit her outreach from her dissertation, but she persisted. There were also efforts to commoditize her Indigenous identity, for example, often being introduced as “the Native student,” which made her ex-imposter syndrome. She didn’t find support for her identity as both a scientist and Indigenous person until she was mentored by Dr. Judi Brown Clarke during her postdoctoral fellowship at Michigan State University. With Dr. Clarke’s encouragement she engaged in programs that gave her a strategic perspective on her goal of bridging two major drivers in her life: her love of geoscience and her commitment to broadening access to science for Indigenous peoples. An AAAS science and technology fellowship place at the National Science Foundation’s STEM Education Directorate broadened her knowledge of funding decisions for Native American education programs and allowed her to lend her expertise on tribal government structure and operations via workshops for NSF program officers.

Interweaving Two Ways of Knowing

As her community reclaims their heritage, Dr. Todd is reconnecting with hers by learning to speak the Haida language, and not only teaching Western Science to Native Alaskans but trying to help all people understand the science within Native stories. In one such story about Raven (often a trickster in Pacific Northwest Native stories) and water, she explains that it is a metaphor for the earth’s water cycle and ties the animacy of the water in the story to concepts such as geology, geography, and hydrology to show how water carves out the earth and impacts the environment.

At this point in her journey, Dr. Todd arrived at a place where her model for using these two very different epistemologies and methodologies is one of interwoven domains. As she and her coauthors propose in a 2023 paper, “The center of the model is the TK component as the core of Indigenous students’ worldviews and meaning making, encompassing all disciplines simultaneously along with cultural values and spirituality.” True to her Indigenous-centered holistic perspective, the core then is interwoven with all academic disciplines that are themselves interwoven among each other. This model will serve as the canoe’s guide as she steers her inaugural program on Indigenous Science into the waters near Hydaburg.

“The center of the model is the TK component as the core of Indigenous students’ worldviews and meaning making, encompassing all disciplines simultaneously along with cultural values and spirituality.” Todd, Towne, and Clarke in Journal of Geoscience Education 2023.

Books recommended by Dr. Todd on Indigenous Sciences and Experiences

- Cajete, G. 2016. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Clear Light Publishers.

- Hernandez, J. 2022. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes through Indigenous Science. North Atlantic Books.

- LaDuke, W. 2016. All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life. Haymarket Books.

- Nelson, MK and Shilling, D. 2021. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability. Birch Bark Books.

- Smith, LT. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zen Books.

- Wilson, S. 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

Indigenous Science and Two-Eyed Seeing

A Quick Compare and Contrast

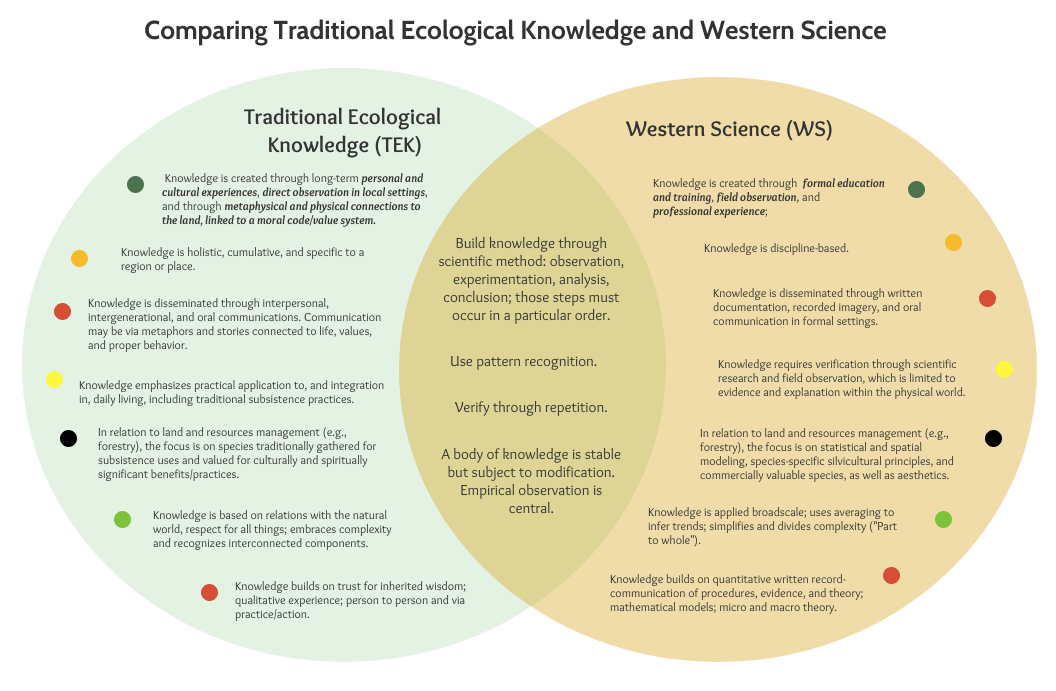

A good model to compare and contrast Western and Indigenous science is in the field of ecology, where the distinctions seem to outnumber the commonalities.

Indigenous Knowledge Acknowledgement

Western or “modern” science, with its formal development attributed to classical Greece and centered on discipline-based, context-independent empiricism, and Indigenous science, which is centered on place-specific lived experiences, are two very different ways of understanding the natural world. However, as part of the growing social justice movement for Native American civil rights that was accelerating in the 1970s, two Indigenous-focused STEM organizations, Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science and American Indian Science and Engineering Society, led the charge to increase awareness of the validity of Indigenous ways of knowing. And in 1975, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, under the leadership of Dr. Margaret Mead, passed a resolution and published a paper in Science to “formally recognize the contributions made by Native Americans in their own traditions of inquiry to various fields of science, engineering, and medicine.”

Promulgating Two-Eyed Seeing

Today the integration of Western and Indigenous science is being used as one of several multidisciplinary approaches to solve global problems in science such as climate change and sustainable development, and to address increasing the participation in STEM of historically underserved people, including Native Americans, who are the least represented among all racial/ethnic groups in STEM degrees earned in the US.

In 2023, the National Science Foundation awarded a 5-year grant of $30M to establish the Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledge and Science (CBIKS) based at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The Center is committed to “effectively and ethically” braiding or using “two-eyed seeing” to address climate change, food insecurity, and loss of Indigenous cultures.

“Elder Albert indicates that Two-Eyed Seeing is the gift of multiple perspectives treasured by many aboriginal peoples and explains that it refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together for the benefit of all.” Bartlett, Marshall, and Marshall. 2012. J Environ Stud Sci 2:331-340.

A number of schools and organizations are committed to educating Indigenous students in both Western and Indigenous science, including Cal Poly Humboldt’s Indian Natural Resources, Science, & Engineering Program, which “braids science, culture, and community” and the Geoscience Alliance, which “will create ways for students to become scientists while holding onto and even strengthening their traditional knowledge.”

Some Indigenous Science Resources

- Chow-Garcia, N, Lee, N, Svihala, V, Sohn, C. 2022. Cultural identity central to Native American persistence in science. Cultural Studies of Science Education 17: 557-588.

- Kimmerer, RW and Artelle, KA. 2024. Time to support Indigenous Science. Science 383: 243.

- McKinnon, EA and Muth AF. 2024. Introducing a new special section – Indigenous science and practice in ecology and evolution. Ecology and Evolution 14: e11718.

- Todd, WFKS, Northbird, AV, Towne, CE. 2023. The science in indigenous water stories, indigenous women’s connection to water. Open Rivers 23: 7-27.

Editor’s Note: The contents of this article are not affiliated with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Patricia Soochan is a senior program strategist in Data Science, Research, and Analysis in the Center for the Advancement of Science Leadership & Culture at HHMI. In her role, she collaborates with the Center’s programs to capture, analyze, synthesize, and communicate program-level data to promote organizational effectiveness and evaluation. Previously she shared lead responsibility for the development and execution of the Inclusive Excellence (IE1&2) initiative and had lead responsibility for science education grants provided primarily to undergraduate institutions, a precursor of IE. She is a member of the Change Leaders Working Group in the Accelerating Systemic Change Network and is a contributing writer for AWIS Magazine and The Nucleus. Prior to joining HHMI, she was a science assistant at the National Science Foundation, a science writer for a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, and a research and development scientist at Life Technologies. She received her BS and MS degrees in biology from George Washington University.

Patricia Soochan is a senior program strategist in Data Science, Research, and Analysis in the Center for the Advancement of Science Leadership & Culture at HHMI. In her role, she collaborates with the Center’s programs to capture, analyze, synthesize, and communicate program-level data to promote organizational effectiveness and evaluation. Previously she shared lead responsibility for the development and execution of the Inclusive Excellence (IE1&2) initiative and had lead responsibility for science education grants provided primarily to undergraduate institutions, a precursor of IE. She is a member of the Change Leaders Working Group in the Accelerating Systemic Change Network and is a contributing writer for AWIS Magazine and The Nucleus. Prior to joining HHMI, she was a science assistant at the National Science Foundation, a science writer for a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, and a research and development scientist at Life Technologies. She received her BS and MS degrees in biology from George Washington University.