When we look up to the stars, we think the night sky is for everyone. Astronomer Dr. Julianne Dalcanton believes this to be true and has spent her career trying to understand the mysteries of space, while helping make room for others who want to join in this journey.

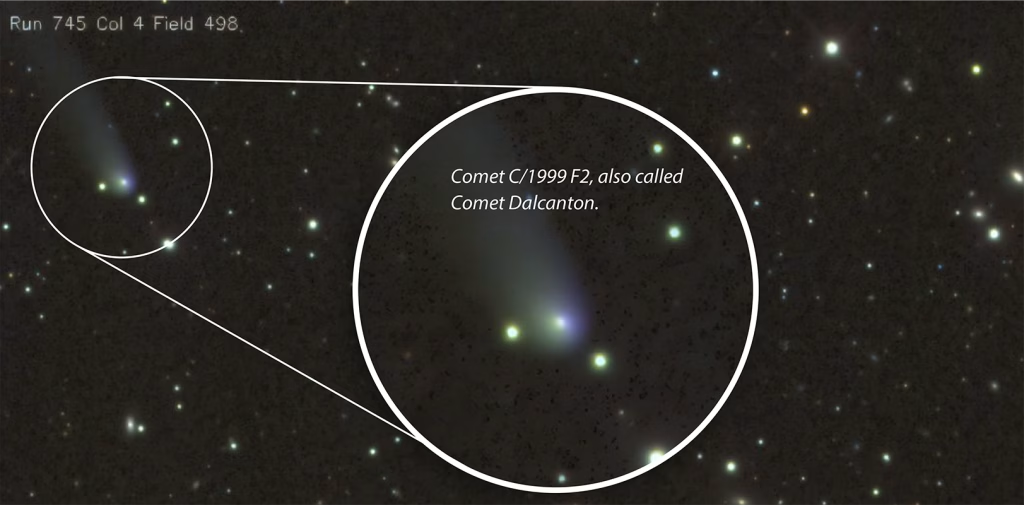

Dr. Dalcanton focuses her research on galaxy formation and evolution with an emphasis on stars, gas, and their interactions. She also explores the extremes of galaxy formation. Early in her career, when analyzing data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) to find unusually broad, faint galaxies, she accidentally discovered a comet, Comet C/1999 F2, later named Comet Dalcanton in recognition of her identification. Comet Dalcanton orbits close to the Sun approximately every 136,000 years, in contrast to Halley’s Comet, which returns every 76 years.

Currently, Dr. Dalcanton is the Director of the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) at the Simons Foundation, while she uses the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to continue her research on large surveys of the nearest galaxies. She has previously held the position of Professor and Chair of Astronomy at the University of Washington, where she worked for over two decades. Dr. Dalcanton received the Beatrice M. Tinsley Prize in 2018 for her outstanding contributions to the field of astronomy and her exceptionally creative character.

Dr. Dalcanton demonstrates this outstanding character by participating in outreach programs aimed at encouraging women in science. She openly shares her life experiences as a professional scientist who navigates work, caretaking, and disability. Through her work and contributions to outreach programs, Dr. Dalcanton aims to help build spaces that allow scientists to bring their whole selves to their professional work. This year, at the American Physical Society Conference for Undergraduate Women and Gender Minorities in Physics (CU*iP) at Stevens Institute of Technology, she delivered an inspirational talk titled “Life as an Astronomer” that helped encourage many women undergraduates to consider careers in astronomy. Dr. Dalcanton has also written for popular science outlets, including Discover. Her hard work and persistence prove that one can achieve extraordinary success. Below is an edited conversation with Dr. Dalcanton, where she shares insights about her work and offers an inspiring message to women in STEM.

The first image of the black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier M87 by the Event Horizon Telescope was a groundbreaking milestone since it confirmed long-standing theories and offered proof of the black hole’s existence. With so many mysteries still hidden in the universe, what inspired you to pursue a career in astronomy?

I went to a large public high school that had a really good science community, with many activities students could participate in. I was involved in many math, chemistry, and physics extracurriculars, but physics was always my favorite. As an undergraduate student at MIT, I worked for my quantum professor, Claude Canizares, who specialized in astrophysics. I worked in his experimental lab that focused on a project related to X-ray detection. During that time, I also worked with a graduate student, Kathy Flanagan, who took me under her wing. While working with instrumentation, I realized that theoretical project work would suit me better than the experimental work. So, I switched from my senior thesis with Professor Canizares to work on gravitational lensing of quasars, which can be used to constrain compact dark matter. I then applied for graduate school, but I was burnt out from undergraduate study and unsure whether I truly liked astrophysics, or whether I was settling for something I had wandered into accidentally. In the meantime, I got a job in industry and worked for a company making high-resolution MRI scanners, where I learned programming and helped develop algorithms. After gaining some experience in industry, I decided to go to graduate school to pursue a career in astrophysics, which I had truly missed. It was also nice to have more flexibility in working schedules [in academia] compared to that of industry.

Modern telescopes are highly advanced in technology, capable of seeing farther than ever, and allow us to view the universe with extreme clarity. How are the HST and SDSS used in modern astronomical research?

The SDSS uses a ground-based telescope that covers very wide areas of the sky, providing highquality data that researchers can use for scientific discoveries. The SDSS has mapped the sky in detail to determine the positions, brightness, and spectra of hundreds of millions of celestial objects

In contrast, Hubble does not cover wide areas of the sky; instead, it focuses on a small field of view, which limits its ability to do large surveys. It has much higher angular resolution than SDSS, however, because of its location above the earth’s atmosphere.

Additionally, HST’s location gives it a lower background in the infrared and the ability to detect ultraviolet photons that would have been blocked by Earth’s atmosphere. Hence, the HST can observe more detailed information than SDSS, but not over the whole sky. Now, we also have the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is larger and better for infrared observation. I would say the HST and JWST complement each other, offering a better perspective of the universe.

Would you share your current astronomical research and its potential impact on our understanding of the universe?

Currently, I am working on a lot of science that takes advantage of the intersection between what we can learn about stars with the HST and the JWST, for example, the identification of young stellar objects (YSO) candidates in the Messier 33 (M33) spiral galaxy, which is the second closest large galaxy to our Milky Way galaxy. YSO candidates help astronomers study the star formation processes in a galaxy with higher sensitivity. An upcoming space telescope called the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) will have wavelength coverage similar to that of the HST. The HWO will have a larger mirror than the HST, so fainter cosmic objects will be visible. It will also have a better angular resolution, due to the more favorable ratio of wavelength to diameter. The HWO will also be optimized for detecting exoplanets that might be habitable, those that have a rocky surface and liquid water. Although exoplanets are not something I study personally, the discoveries that HWO could make would be transformative.

Would you like to share how you tackle complex problems in your research?

I love solving puzzles, and astrophysics is full of interesting questions. Finding answers usually requires first knowing a solution might be possible, and then gathering the bits and pieces needed to make sense of the problem. In the context of research, this sometimes means assembling a team of people and ensuring that everyone works together toward a common goal. Often, collaborating within an organization is essential to solving a puzzle effectively.

Astronomy often involves long nights and intense research. How do you manage the work-life balance in such a demanding field?

I have faced many challenges that resonate with other women’s experiences in navigating professional and personal responsibilities. I am a mother of two, and I took care of my elderly parents. At times, balancing everything has been difficult. However, I have always tried to work in a good environment and with good people, which leads to more effective teamwork. I naturally tend to work hard but have clear boundaries about what I will and won’t do. These boundaries include dedicating weekends to what truly matters to me and spending evenings with my family. I often worked after my kids went to bed. My partner has been incredibly supportive and has never made me feel guilty about pursuing my career goals. I was fortunate that I transitioned my work to space-based observations, which significantly reduced the need for travel. Although it was accidental, it worked out very well for me personally

Did you have any mentor who influenced your career? What advice would you give young women considering a career in astronomy or in other STEM fields?

When I began my career, there were not many women in astrophysics. Professor Canizares from MIT during my undergraduate program and my graduate advisor at Princeton University, Professor David Spergel, were two mentors who helped me to pursue my career in astronomy. Princeton also had a few senior women faculty, which was unusual at the time, and helped create a good atmosphere. I also benefited from a strong peer network of mentors, particularly later in my career. My biggest advice for younger women navigating their careers at a faculty level is to cultivate a supportive peer network. You will invariably face complicated issues that are new to you, and it is helpful to have people whom you trust and who understand you. Most importantly, pursue work that you love to do. If it is miserable, you don’t have to keep doing it. It is okay to make choices that are based on what you enjoy. For instance, I transitioned from industry back to academia because I realized that certain aspects of industry didn’t suit me. Academia with research and mentoring opportunities felt like a better fit. That said, what works for me might not work for someone else with a physics or astronomy background. So, pick the field and style of work that aligns with your interests and temperament, so that you can truly enjoy your work.

Do you have any recommendations for specific skills or experiences that are essential for success in the field of astronomy?

I would say good computer skills are always helpful because astronomy is a data-rich field. That means one can access the data from large surveys and analyze it for interesting science projects that no one else has done. Unlike laboratory-based sciences like chemistry or biology, astronomy usually relies on interpreting data rather than on conducting physical experiments. If you are comfortable working with complexity, you will f ind astronomical data analysis rewarding.

In what ways do you think artificial intelligence could reshape our understanding of astronomical discovery?

As mentioned previously, computational tools are important in various research areas in astronomy. Unsurprisingly, machine-learning techniques have already proven to be useful tools, particularly in handling and interpreting data, and more recently in simulations. This acceleration in data analysis can lead to faster scientific discoveries. While AI can flag anomalies in data, it is still human astronomers who design experiments to explain hypotheses, interpret results, and provide scientific context. I would say AI is a tool that complements astronomers’ efforts, rather than a replacement.

Innovative light-sound devices helped low vision people to experience the solar eclipse in 2024. How can we further enhance the accessibility and inclusivity in astronomy for a broader audience?

Yes, there are a lot of innovative projects. A postdoctoral researcher in our organization, Carrie Fillion, is hosting an upcoming sonification conference, finding ways to translate the complexity of images into complex sounds that encode information. Other colleagues have created 3D tactile models of astronomical structures. Tools like audio and 3D-printed models allow astronomers to create auditory and tactile experiences for the visually impaired or for those who learn better through these means. Other astronomers are investing in ways Yes, there are a lot of innovative projects. A postdoctoral researcher in our organization, Carrie Fillion, is hosting an upcoming sonification conference, finding ways to translate the complexity of images into complex sounds that encode information. to make astronomy accessible in underserved rural communities, where people might have beautiful views of the night sky but face obstacles to accessing science in an approachable way

Would you like to say what your hopes and dreams are for the future of astronomy, particularly for the role of women in this field?

When I attend meetings of the American Astronomical Society, I see a much richer representation of humanity than I did when I started my career, which brings me joy to see. I want astronomy to be a field where spaces are filled with people who have the opportunity to pursue what they love—not just those who managed to survive. That means seeing more people of all backgrounds and genders enter astronomy, lead major research initiatives, and mentor the next generation. I want this field to be inclusive so that people who are passionate about astronomy don’t have to leave because they couldn’t f ind a workspace environment that welcomes who they are. The universe belongs to all of us, and our science grows stronger when every voice is heard and when every talent is valued.

Shruti Shrestha, PhD, is an Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics at Penn State Brandywine. She is a particle physicist who worked on the High Voltage Monolithic Active Pixel sensor for the Mu3e Experiment. She also conducts free STEM workshops in the Philadelphia area to empower girls to pursue STEM degrees.

Shruti Shrestha, PhD, is an Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics at Penn State Brandywine. She is a particle physicist who worked on the High Voltage Monolithic Active Pixel sensor for the Mu3e Experiment. She also conducts free STEM workshops in the Philadelphia area to empower girls to pursue STEM degrees.

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.