In the realm of science and technology, we think of a serendipitous discovery as an unplanned, usually fortunate breakthrough made without the intention of doing so. Scientific progress generally requires an intentional approach and often stems from the meticulous study of niche and specific topics, many of which appear irrelevant or unimportant to the average person’s everyday life.

These discoveries, however, can lead to novel transformative breakthroughs with widespread impact, which can deepen our understanding of the fundamental principles of science and medicine. For instance, in 1898, Marie and Pierre Curie discovered the radioactive elements radium and polonium while investigating the properties of uranium ores, and Marie Curie became the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize for her role in the discovery. Their pioneering research laid the foundation for the field of radioactivity. Within a few years, scientists harnessed the unique properties of radium in cancer treatments, marking a significant advancement in medical science.

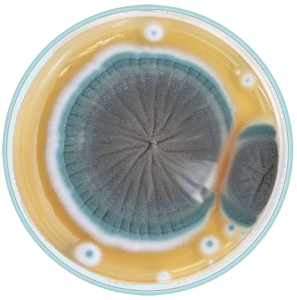

One of the more salient examples of a serendipitous scientific discovery involved the development of the antibiotic penicillin. During the 1920s, a bacteriologist named Alexander Fleming accidentally stumbled upon the discovery when he returned from a vacation and noticed mold had contaminated some of the petri dishes that he had placed samples in. The mold, later identified as belonging to the genus Penicillium, prevented his bacterial samples from growing around it, which led to his conclusion that the fungus had antibacterial properties. Fleming identified the active agent, which he named penicillin, and published his findings in 1929. Despite this, the purification of this agent proved beyond his capabilities, and doctors did not administer penicillin to humans until 1941. In 1945, Fleming received the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for the discovery, along with Ernst Boris Chain and Howard Walter Florey, for their additional research.

Other scientists introduced CRISPR-Cas9 technology, another fortuitous byproduct of microbiology research, in the early 2010s and revolutionized biotechnology by providing a method for editing genomes. In 2020, Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier and Dr. Jennifer Doudna received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, and they were the first two women to jointly win the prize. Commonly thought of as “genetic scissors,” CRISPR-Cas9 allows for the insertion or deletion of genes into a genome, which has implications for research, medicine, and agriculture. The origins of CRISPR-Cas9 lie in microbiology, with the technology modeled on the microbial adaptive immune system. CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) refers to a family of DNA sequences first discovered in the 1980s in the bacteria Escherichia coli. These sequences represent DNA fragments from bacteriophages and viruses that invaded the bacteria or their progenitors which integrate into the bacterial genome as an adaptive immune defense. Scientists later discovered Cas9 (CRISPR associated protein 9), the protein that “cuts” the DNA, in Streptococcus thermophilus, a bacterial species of interest due to its role in producing fermented milk products such as yogurt. This prokaryotic immune mechanism laid the groundwork for the development of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology.

Just as CRISPR-Cas9 changed the biotechnology field as we know it, groundbreaking discoveries in prenatal biology began to reshape the framework of prenatal care. Fetal microchimerism refers to the presence of fetal cells in the mother’s body, which can persist for decades after childbirth. Initially considered an anomaly, this phenomenon has led to a deeper understanding of maternal-fetal interactions and has implications for autoimmune diseases, cancer biology, and regenerative medicine. While the work proved challenging due to the relative rarity of the fetal cells in the mother’s blood, the research led to an unexpected finding. Dr. Diana Bianchi discovered that intact fetal cells remain in the mother’s blood and organs for decades following pregnancy and may migrate to the site of an injury to help repair it. The discovery of fetal microchimerism has profound implications for prenatal care. It has led to the development of noninvasive prenatal tests (NIPTs) that analyze cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood, allowing for early detection of genetic conditions without the risks associated with invasive procedures like amniocentesis.

In a different realm of science, Dr. Peter Higgs and other researchers theorized in 1964 about how particles acquire mass, which led to the discovery of the Higgs boson, often dubbed the “God particle.” Its confirmation in 2012 at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider completed the Standard Model of particle physics, providing a critical piece in understanding the fundamental forces of nature. This discovery not only deepened our comprehension of particle physics but also spurred technological advancements in computing, medical imaging, and cancer treatment, demonstrating how a single scientific breakthrough can ripple across various fields, much like the profound impact/implications of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and fetal microchimerism in medical science.

These discoveries, though vastly different in scale and context, highlight how rare scientific discoveries can ripple across seemingly unrelated fields, offering new insights and applications that extend well beyond their initial scope.

Hannah Fricke, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School and holds a PhD in Endocrinology and Reproductive Physiology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current research focuses on reproductive hormones and sexual dimorphisms in osteoarthritis, and she has a background and passion for science communication.

Hannah Fricke, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School and holds a PhD in Endocrinology and Reproductive Physiology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current research focuses on reproductive hormones and sexual dimorphisms in osteoarthritis, and she has a background and passion for science communication.

Tamara Mestvirishvili holds an MS in Biology from New York University with a focus on Bioinformatics and Systems Biology. She also earned a BS from City College and conducted post-baccalaureate studies at Columbia University, and she now works as a bioinformatics analyst at NYU Langone Medical Center. She has mentored at the New York Academy of Science and is currently Science Communicator for LifeSci NYC.

Tamara Mestvirishvili holds an MS in Biology from New York University with a focus on Bioinformatics and Systems Biology. She also earned a BS from City College and conducted post-baccalaureate studies at Columbia University, and she now works as a bioinformatics analyst at NYU Langone Medical Center. She has mentored at the New York Academy of Science and is currently Science Communicator for LifeSci NYC.

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.