Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein could not have a first name more perfect for who she is and what she does.

Chanda, a Sanskrit word in The Yoga Sutra (the authoritative text on yoga), means “moon” and the idea that if one concentrates on the moon, one obtains knowledge of the stars. Fittingly, Dr. Prescod-Weinstein is an associate professor of physics and astronomy, as well as a core faculty member in women’s and gender studies at the University of New Hampshire. Her name aptly reflects her research in cosmology and particle physics.

More specifically, her research in theoretical physics focuses on cosmology, neutron stars, and dark matter (DM). She is also a researcher in Black-feminist science, technology, and society studies. Among her recent roles, Dr. Prescod-Weinstein was a co-convener of Dark Matter: Cosmic Probes in the Snowmass 2021 particle-physics community-planning process and a National Academies Elementary Particles: Progress and Promise decadal committee member. She created the Cite Black Women+ in Physics and Astronomy Bibliography.

In addition, this talented scientist has gotten attention for her advocacy work. Nature recognized Dr. Prescod-Weinstein as one of 10 people who shaped science in 2020, and Essence magazine has recognized her as one of “15 Black Women Who Are Paving the Way in STEM and Breaking Barriers.” A co-creator of the Particles for Justice letter against sexism in particle physics and of the 2020 Strike for Black Lives, she received the 2017 LGBT+ Physicists Acknowledgement of Excellence Award for her contributions to improving conditions for marginalized people in physics, as well as the 2021 American Physical Society Edward A. Bouchet Award for her contributions to particle cosmology.

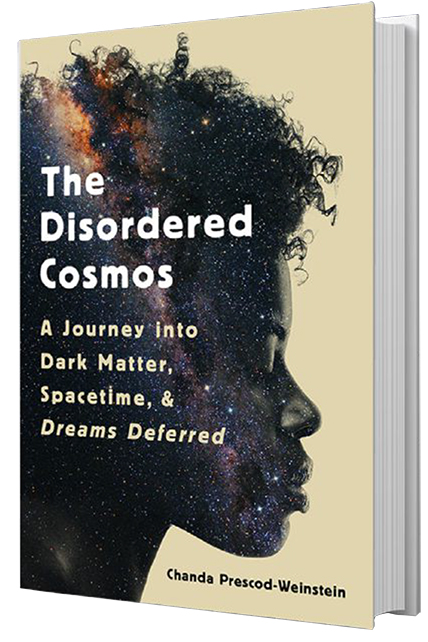

Dr. Prescod-Weinstein is also a columnist for New Scientist and Physics World. Her first book, The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred (Bold Type Books), won the 2021 Los Angeles Times Book Prize in the science and technology category, the 2022 Phi Beta Kappa Science Award, and a 2022 PEN/Oakland Josephine Miles Award. It was named a Best Book of 2021 by Publishers Weekly, Smithsonian Magazine, and Kirkus Reviews. In 2022, Dr. Prescod-Weinstein was the inaugural top prizewinner in the mid-career researcher category of the National Academies Eric and Wendy Schmidt Award for Excellence in Science Communication.

This writer, scientist, and advocate is originally from East Los Angeles but now divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts—where she has a research affiliation with the Science and Technology Studies program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology— and the New Hampshire seacoast. The following is my recent, edited interview with her.

Shruti Shrestha: We do not require statistical details to convince us that women are underrepresented in STEM, particularly in physics. What motivated you to stay focused on becoming a physicist?

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein: When I was ten years old, my mom took me to see a documentary by Errol Morris called A Brief History of Time. It focused on pioneering astrophysicist Stephen Hawking. At that point, I was excited about math but didn’t know much about physics. I didn’t want to see the documentary; I wanted to stay home and watch Saturday morning cartoons instead. Halfway through the film, Stephen Hawking talked about how his work focused on solving problems about black holes that Einstein hadn’t worked out.

His contribution to Einstein’s theories was to describe the physical characteristics of black holes and to explain that when a star collapses, it forms an infinitely dense point called a singularity. He used mathematics as a tool to describe black holes, and I felt [excited knowing that] you could get paid to do math all day. Math describes the universe, and you get to work on problems that Einstein worked on. That was how I decided that I wanted to be a theoretical physicist, a job that seemed like the best one, so I came out of the movie theater begging my mom for a copy of Hawking’s book.

SS: A report by the American Institute of Physics mentioned that women were 19% of physics faculty members and 23% of astronomy faculty members in 2018. Did you have any female physics professors when you were in undergraduate and graduate programs?

CP-W: When I started the undergraduate program at Harvard University, there were only two woman faculty members in the physics department. One of them was Professor Melissa Franklin, an experimental particle physicist. She was my undergraduate adviser. The other, Professor Lene Hau, was hired during my sophomore year and taught the undergraduate second-semester quantum mechanics course. She was the only female professor who taught me in my entire higher education. A decent number of female students were in undergraduate physics and astronomy classes. Among the women in our group, Michelle Dolinski (now a physics professor at Drexel University), Ann Marie Cody (an astronomer), and I became professionals in physics and astronomy.

SS: Most of the time, gender bias may happen in subtle ways, like people overlooking you in professional environments and not taking your technical skills seriously. Did you experience any gender bias as a student or at your workplace? What is it like to be a woman of color in science? What do you suggest for better implementing policies against gender bias in STEM?

CP-W: I have so many stories to share, but figuring out what to say in response to this question could be hard. When I was in college, one of the things I learned early on was that jokes about sex were a normal part of being in a physics study group with men. Basically, they were teenage boys when they started, and I struggled in that kind of environment, where it was normal to talk about women’s body parts.

When I got engaged to my ex-wife, my professor asked me a bunch of invasive questions about my sexual attraction to men. I do not know if that was gender bias because I felt he would have asked the same types of questions of others. But undoubtedly, there are just ways that people make you feel uncomfortable. It can feel dehumanizing.

Also, not long after I graduated from college, the president of Harvard University, Larry Summers, commented on whether women had the same capacity to do science as men, so suddenly, it was a national news story about whether women were as good at science as men. It is a different experience trying to focus on science while the whole country is discussing whether you can do it or not. This happened again when a Supreme Court justice asked whether Black students belong in physics classrooms. So again, there was an extensive conversation about Black people in physics, and I was like, I want to do physics, but is the whole country discussing whether I am smart enough to actually do physics?

To advance and to maintain women in STEM fields, family-leave policies should be supportive since women are the ones carrying a child to term and need this help to continue a career, or they have to rely on family support. Another problem, unfortunately, is that some people have a machismo attitude about doing and talking about physics, but American women want to collaborate with others. I think it would be helpful if science were highly collaborative rather than combative.

SS: Several astrophysical and cosmological observations indicate the existence of dark matter or DM, which predominantly constitutes galaxies and other structures in the universe. However we still haven’t definitely identified its composition and properties. You have a recently published paper in Physical Review D on “Constraining bosonic asymmetric dark with neutron star mass-radius measurements.” Can you explain why neutron stars may allow us to probe certain types of DM?

CP-W: We see a lot of visible matter in the universe, but it contributes only about 20% of all gravitating matter. The rest of the gravitating matter in the universe is invisible matter, which we call dark matter since it does not interact with electromagnetic radiation. Understanding the composition of DM and its properties is the biggest open question in cosmology. Since DM is invisible, finding information about it differs from what we usually do: we grab a specimen, put it in a lab, and shake it.

One person I collaborate with on dark matter is Anna Watts, Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Amsterdam, who works on neutron stars. I got interested in how we could use neutron stars to understand DM. Neutron stars are remnants of stellar death. They are so dense that they can pack more than the mass of the sun in a sphere the size of Los Angeles County. Furthermore, neutron stars got their name because their cores have such powerful gravity that positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons in the interior of these stars combine into uncharged neutrons.

These neutron stars are ideal cosmic labs that help astronomers study DM under extreme conditions (high temperature and pressure) since we cannot reproduce such an environment on Earth. They are so dense that they may be able to trap all the dark matter particles that pass through them. In [our current] paper, we explore the effects of dark matter on neutron stars by looking at the percent change in mass and radius of a neutron star with and without a dark-matter core, based on a theoretical model.

SS: In your PhD dissertation, Cosmic Acceleration as Quantum Gravity Phenomenology, you mention the cosmological constant and dark energy. Dark matter and dark energy have similar names: how are they different from each other?

CP-W: Cosmologists believe that about 95% of the energy-matter content in the universe is composed of DM and dark energy. Like DM, dark energy does not emit light and thus is not visible in telescopes. However, its properties differ significantly from those of dark matter. In 1998, scientists discovered that the universe is expanding at an increasing rate, and dark energy is a term that describes a probable answer to this open question in observational cosmology: why is the expansion of the universe accelerating? Our simplest explanation is that an energy associated with empty space is causing this expansion to go faster. This has come to be known as dark energy. This form of energy exerts a negative, repulsive pressure, behaving like the opposite of gravity.

We know very little about dark matter and energy, despite the fact that both make up almost the entire universe. There are numerous experiments worldwide to gain a deeper insight into the nature of DM and into the role of dark energy in expanding the universe. Scientists are optimistic about making a breakthrough in upcoming years.

SS: You are also a member of the Spectroscopic TimeResolving Observatory for Broadband Energy X-rays (STROBE-X) probe program. What is the mission of STROBE-X? How are you involved in it?

CP-W: STROBE-X is a mid-sized space telescope planned by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). It will provide an unprecedented view of the X-ray sky by performing timing and spectroscopy over the broad energy band (0.2–30 keV) and over a wide range of timescales, from microseconds to years. It will help us to understand more about black holes and neutron stars and will contribute to extragalactic science. I am a part of the steering committee leadership and am the co-leader for cosmology and extragalactic astronomy.

SS: As a scholar who publishes scientific writings and books, what texts might you recommend for young students and nonacademic adults interested in astronomy or astrophysics?

CP-W: Firstly, I would like to recommend my book, The Disordered Cosmos. Next, I am a big fan of Katie Mack’s The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking). It is a great book, and you don’t have to be anxious about trying to read it, even if you’ve had a bad experience with math. The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy by Moiya McTier is also good. It gives the background science of the galaxy to a general audience.

SS: Your award-winning book, The Disordered Cosmos, is a tour of particles like quarks, leptons, and dark-matter candidates and of your path to becoming a physicist and an activist. You have a chapter in this book called “Physics of Melanin” in which you discuss colorism. Why is this topic important to discuss? What kind of audience should read it, and why?

SS: Your award-winning book, The Disordered Cosmos, is a tour of particles like quarks, leptons, and dark-matter candidates and of your path to becoming a physicist and an activist. You have a chapter in this book called “Physics of Melanin” in which you discuss colorism. Why is this topic important to discuss? What kind of audience should read it, and why?

CP-W: Initially I had thought about melanin in terms of physics, about how it interacts with light. That is, I was interested in the spectroscopy of melanin. That is how I thought of this chapter.

When the hardcover book came out, I read the chapter and was not happy with it. When preparing the paperback version, I changed it. However, I wrote this chapter three times and could still rewrite it. It is because when I first wrote about the “Physics of Melanin” for a magazine before using the content [to develop] this book, I was very focused on science, and then when I sat down to work on the book, there were many protests happening. There was a tension between wanting to be excited about the beauty of melanin and acknowledging the complicated feelings that people have about their melanin. Hence, that chapter is dynamic because my thoughts about where the emphasis [should be are] constantly changing.

I want the book to be for everyone, but in particular, it is important for me to make sure that Black audiences feel that they are thought of and spoken to. I never thought the only readers for my book would be Black people or anything like that. When readers pick up my book, I would like them to feel that the author thinks of them and that the book expresses all the different ways that Black lives matter and that Black curiosity matters.

This book is also a bit like a Trojan horse. That is, if you pick it up because you are interested in science, you are also going to learn some feminist theory and critical race theory. If you pick up the book because you are interested in feminist theory or critical race theory, you are going to learn some science.

SS: Many influential women of color made groundbreaking discoveries in STEM. Katherine Johnson and Dr. Gladys West were experts in their fields and contributed to the success of their organizations and institutions. What are your suggestions for girls of color that encourage them to go into STEM, based on the experiences you’ve had? How can their participation in science be increased?

CP-W: The one piece of advice I want everyone to hear is that you are the one to decide to pursue physics; somebody else should not choose this for you. If you do not love physics and are not interested in it anymore, that would be the reason to walk away. [But deciding that you cannot stand with other scientists] is a terrible reason to quit because your curiosity is yours, and no other people should decide whether you get to spend time being curious about the universe. [I also want to say that] STEM is not just for girls of color but is for everyone. Furthermore, [I encourage everyone to speak] with multiple mentors: having multiple mentors helps you to learn from different perspectives, which helps you to understand the concepts better.

I have a Pakistani American friend who was saying recently that so many of the Black students come and talk to her because they see her as a brown woman who probably understands something of their experience. It is crucial for us to engage in this kind of solidarity and to recognize that even when we do not have the same identity as a student, there may be aspects of their identity that we can speak to and that we may share. For example, I always tell my students at some point that I was a federal work-study student. I was a Pell Grant student, and the students in my class who have Pell Grants may feel that I understand that aspect of their experience. So, there is an element of making yourself available by being not just professional but by humanizing yourself instead of just being an authority in the room. Educators can support Black and brown girls by creating communities that encourage them to feel comfortable, welcomed, and supported.

SS: Do you have any advice for women beginning their careers in STEM? Possibly something you wished you had known when you first started.

CP-W: When I was in a workshop for women on how to apply for faculty positions, one of the panelists said that if you are going to be romantically involved with someone, choose wisely. It will significantly affect your ability to focus on your work. At that time, I thought that was a strange piece of advice. But now I think about that suggestion a lot.

University research culture, the demand for teaching and research work, and the immense pressure to publish papers and to win research funding leave people in academia experiencing high stress levels. Practically, having a spouse who supports what I do and takes the time to understand the pressure has made a huge difference in my ability to do my job. I think we don’t talk about this issue often.

SS: You were a founding member of the American Astronomical Society’s Committee for SexualOrientation and Gender Minorities in Astronomy (SGMA). How were you involved in this committee? Do you think a person’s race, gender, and sexuality can be a benefit or a cost in doing scientific work?

CP-W: I was a founding member of SGMA and an executive member for a full term (three years). During this time, the committee worked to have a community for LGBTQIA+ people in astronomy and to make it easier for people to find each other and to be visible so that it would be convenient to speak up.

I do not think that there is something in our DNA that makes those of us who are female-identified and queer do science differently. Still, I do believe that the ways people respond to your sexual orientation or race, and the way you identify with other members of a community, certainly shape how you engage with the world. An example of a strength that people don’t necessarily think about is that I was used to going into spaces where people might diminish me by asking challenging questions to check on my knowledge of science, because they viewed me as Black or as a woman or as queer. Such situations prepared me to handle anything. I think they taught me to be a prepared person for better or for worse.

SS: In Scientific American magazine, you wrote an article titled “The James Webb Space Telescope Needs to be Renamed.” Why do you think its name should change? What name would you change it to?

CP-W: I like to call it Just Wonderful Space Telescope because it is an awesome telescope, and the acronym JWST matches the current name. JWST is an extraordinary piece of equipment, primarily an American-led mission. When we put ourselves among the stars, what memories and stories should we send up to them? I actually think the name should be dedicated to someone who used astronomy for freedom to take people out of slavery. Harriet Tubman Space Telescope would be an ideal name for this telescope. She was an enslaved person and abolitionist, and she earned the nickname Moses for liberating so many enslaved people at significant risk to her life. Stories about her say that she used the Big Dipper and the North Star to guide slaves out of the South to freedom in the North.

SS: You have won numerous awards for your creative work. What accomplishments are you most proud of?

CP-W: I am proud of making significant enough contributions to earn tenure. I can see some of the scientific impact that I have had on the field of cosmology in understanding the nature of the axion, which has become the prime particle candidate for DM. Furthermore, I am proud of my published and two upcoming books. One of the new books is named The Edge of Space-Time, and it is intended for general audiences. The other one is called The Cosmos is a Black Aesthetic, an academic book. This book will extend the philosophy of Black aesthetics to articulate science as part of the broader picture of Black aesthetics. I want to push us away from the narrative that Black people have not been doing science and are new to science and to restore a sense that science has long been part of Black thought and Black intellectual work.

SS: How can AWIS members support or get involved in your initiatives?

CP-W: I am hesitant to tell women to do more because women do so much already with academics, housework, and the scientific community. Professional women have expanded their careers in male-dominated fields. I hope AWIS will amplify its efforts to talk about how, disproportionately, women carry the load of emotional and even physical housework in academia. That is an important topic through which we should be trying to articulate a new vision of what it means to be a professional, and it shouldn’t be with reference to old systems that didn’t work well for us.

Shruti Shrestha is an Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics at Penn State Brandywine. She is a particle physicist who worked on the High Voltage Monolithic Active Pixel sensor for the Mu3e Experiment. She also conducts free STEM workshops in the Philadelphia area to empower girls to pursue STEM degrees.

Shruti Shrestha is an Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics at Penn State Brandywine. She is a particle physicist who worked on the High Voltage Monolithic Active Pixel sensor for the Mu3e Experiment. She also conducts free STEM workshops in the Philadelphia area to empower girls to pursue STEM degrees.

LINKS

- Personal website: http://chanda.science

- The Disordered Cosmos U.S.

CONTACTS

- Agent: Jessica Papin, Dystel, Goderich, & Bourret LLC, jpapin@dystel.com

- North America Publicity: Jocelynn Pedro, 212-364-0680, jocelynn.pedro@hbgusa.com

- U.K. & Ireland Publicity: Victoria Gilder PR, victoriagilderpr@gmail.com, 07841 678503

This article was originally published in AWIS Magazine. Join AWIS to access the full issue of AWIS Magazine and more member benefits.